Prison Abolition In Practice

--Part two of an interview with Criminal Injustice

By

Focusing on the prison abolitionist movement, we interview two co-editors of an exciting new series at Daily Kos, called Criminal InJustice Kos, a weekly series "devoted to exploring the myths of 'crime', 'criminals', and criminal justice and the intersection of race/ethnicity/class/gender/sexuality/age/disability in policing and punishment. Criminal Injustice Kos is committed to furthering action towards reducing inequity in the

Here, in the second part of our interview, we focus on the practicality of prison abolition and look at alternatives to the

Kay Whitlock (whose online name is “RadioGirl”) is a Montana-based writer, organizer, and activist long engaged in progressive struggles for racial, gender, queer, environmental, and economic justice. She has written extensively on the intersection of race, gender, sexuality, and class in relation to police and prison violence, most notably in her former position as National Representative for LGBT Issues for the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), a Quaker organization. Her publications for AFSC include Corrupting Justice: A Primer for LGBT Communities on Racism, Violence, Human Degradation & the Prison Industrial Complex (pdf download and In a Time of Broken Bones: A Call to Dialogue on Hate Violence and the Limitations of Hate Crimes Legislation (pdf download). With Joey L. Mogul and Andrea J. Ritchie, she is the co-author of Queer (In)Justice: The Criminalization of LGBT People in the

Dr. Nancy Heitzeg (whose online name is “soothsayer99”) is an activist educator and Professor of Sociology and Co-Director of the interdisciplinary Critical Studies of Race/Ethnicity program at

Be sure to read our earlier two-part interview with Heitzeg, published by Truthout, part one: Visiting a Modern Day Slave Plantation and part two: The Racialization of Crime and Punishment.

Angola 3 News: What are practical alternatives to the current prison system? What examples do we have when looking from an international perspective? Examples from here in the

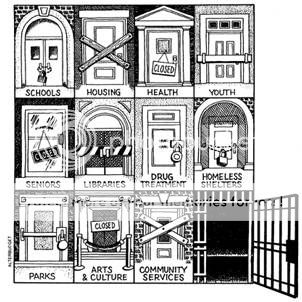

Kay Whitlock: Accumulating overreliance on more policing, harsher punishments, and an expanded prison system to allegedly produce “safety” in our society has effectively shuttered our collective ability to think about justice outside the framework of prisons. There are very few real alternatives for that reason. Clearly, the prison system is not going to be abolished in one fell swoop – that’s not realistic. But we also lack strategic capacity for thinking clearly and synergistically about how to begin interrupting the revolving door, self-perpetuating nature of the criminal legal system. And how to divert resources that otherwise might to into more policing and prisons into broader community safety strategies that also address the needs of communities of color and other groups most likely experience violence within families, communities, and the criminal legal system. These include undocumented immigrants, poor and homeless people in general, people with mental illness, women, youth, queers who challenge middle-class heteronormativity, people with addictions, and more.

There’s no funding for real alternatives. No political will to find them over time. No broad-based faith leadership that calls us to new directions. Possible options are being choked to death by political and religious cowardice and failure of imagination. So that’s our challenge: to find inventive, intriguing, and constructive ways to shake up public discourse and get practical about new directions. To reach outside of that long shadow of prison that deadens our public imagination in order to think in fresh ways about these things and start creating more community capacity to confront multiple kinds of violence – at the hands of individuals, the state, corporations, and a whole host of public/private institutions.

Thank goodness, pockets of real imagination are found in a growing number of more locally based groups and organizations, often led by people from the communities who historically have borne the systemic brunt of police/prison violence. Focusing on strategies that seek to interrupt the revolving-door nature of the criminal legal system and how to divert resources that otherwise might go into more policing and prisons they tackle specific issues such as violence against queers, women, and children in ways that open up broader discussions about the creation of community safety.

Here are just a few groups working from various angles to create community safety without reliance on more policing and prisons:

Creative Interventions (Oakland) (This link is to an interview with CI founder Mimi Kim; I've had trouble recently linking to the Creative Interventions website, which is found here.): Developing community-based responses to domestic and sexual violence in communities of color, queer, and immigrant communities without involving police, as well as strategies aimed at promoting the healthy transformation of all people involved and the larger community.

The Audre Lorde Project: a Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Two Spirit, Trans and Gender Nonconforming People of Color center for community organizing, focusing on the

FIERCE: Building the leadership and power of LGBTQ youth of color; addressing the criminalization of poor, young queers of color in gentrifying areas in NYC by bringing those voices into the center of discussion about planning and safety.

But there also are a few systemic changes that could help enormously.

Nancy A. Heitzeg: During the past 40 years there has been a dramatic escalation the U.S. prison population, a ten-fold increase since 1970. The rate of incarceration for women escalated at an even more dramatic pace. The increased rate of incarceration can be traced almost exclusively to the War on Drugs and the rise of lengthy mandatory minimum prison sentences for drug crimes and other non violent felonies. It is important to note that 75% of all those imprisoned are incarcerated for a non-violent offense.

A similarly repressive trend has emerged in the juvenile justice system. The juvenile justice system has shifted sharply from its’ original rehabilitative, therapeutic and reform goals, into a “second-class criminal court that provides youth with neither therapy or justice.”(Throughout the 1990s, nearly all states and the federal government enacted a series of legislation that criminalized a host of “gang-related activities”, made it easier and in some cases mandatory) to try juveniles as adults, lowered the age at which juveniles could be referred to adult court, and widened the net of juvenile justice.

These harsh policies have proliferated, not in response to crime rates nor any empirical data that indicates their effectiveness,. They have proliferated due to our unfounded fears and the profit motive that is increasingly wound up with the prison system.

The most immediate practical solution is decriminalization of a multitude of lesser and "victimless" offenses and a wholesale return to community corrections – probation, restitution and community service.. Prior to mandatory minimum sentences, these were the primary sentencing options for non-violent offenders. Probation has been used effectively for over 100 years. Community alternatives have long been associated with both much lower costs than incarceration and higher “success” rates as measured by lower recidivism rates. It costs an average of $ 25000 per inmate per year local state fed nearly $150 billion per year and the average execution costs an average of $2 million dollars..Comparatively – community correctional options have one-third of the costs and twice the success rate.

In addition to these well-tried traditional methods, there is also a move to consider restorative justice models. In the context of the community and presented as true alternative to other criminal sanctions, restorative justice models offer a method for actually addressing and repairing torn community relations

There are also international examples we can learn from. Decriminalization of drugs and other lesser offenses reduces stress on legal systems and removes an entire class of offenders form legal control. Prisons are used rarely and sentence lengths are much shorter. Perhaps the best example of how prisons may serve a rehabilitative and reintegrative purpose is Norway's new Halden Fengsel prison, described as the most humane prison in the world.

There are many options available to us other than prison and certainly many uses of prison that are less draconian than those offered in the United States. We merely lack the will to change.

A3N: What examples of organizing against the PIC do you find most inspiring?

KW: The struggle for abolition would not be gaining the ground it is without the vision and relentless persistence of Critical Resistance and INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence Other groups such as the Institute for Community Justice are taking on the challenges of community-led solutions to the crisis of mass incarceration.

I also have a special love for groups that have a genius for refusing to get caught in the “single issue” trap that characterizes much of nonprofit work today by building strong bridges to the challenge of resisting the prison industrial complex. They prove that a single issue is an entry way to cross-issue, cross-constituency movement building. In addition to those groups already named earlier, the groups that most inspire me are:

The Sylvia Rivera Law Project

Queers for Economic Justice

Project Unshackle of the Community HIV/AIDS Mobilization Project (CHAMP)

Committee on Women, Population and the Environment(CWPE Task force on Militarization, Criminalization & Surveillance)

Not surprisingly, these groups are multiracial, center the experiences and voices of people of color and poor folks, and often have strong participation – and leadership - by people who have been incarcerated.

NH: I am inspired by the work of Critical Resistance, The Prison Activist Resource Center and The Real Cost of Prisons Project. All these grassroots groups require justice activists, educators, artists, justice policy researchers and people directly experiencing the impact of mass incarceration to work towards change. These powerful coalitions are the basis for real change.

Davis (1997: 71-72) identifies three key dimensions of this work –public policy, community organizing, and academic research;

“In order to be successful, this project must build bridges between academic work, legislative and other policy interventions, and grassroots campaigns calling, for example for the decriminalization of drugs and prostitution, and for the reversal of the present proliferation of prisons and jails."

I am inspired always by the writings of those who are imprisoned -- Leonard Peltier and Mumia Abu-Jamal, Assata and Sundiata, George Jackson, , Angela Davis, Huey P. Newton, and Stanley “Tookie” Williams, Marilyn Buck, Jimmy Santiago Baca Kathy Boudin and Rita Bo Brown, Wilbur Rideau, and many more.

And I am inspired by those who work to carry these voices to the outside. The writings of many political prisoners/prisoners of conscience might have remained suppressed were it not for the efforts of scholars to bring them forward. This coalition between what Mumia calls “organic and radical intellectuals” is crucial to the uncovering of the deep structural connections between race, political economy and crime.

The work of Angela Davis and Joy James is exemplary here. Their extensive writings on these matters and their careful attendance to connecting with those inside prison walls serve as a model for future work. In Imprisoned Intellectuals (2003), James gives voice to the range of political prisoners and traces the common thread of resistance across generations, nationalities, racial/ethnic differences, genders, sexual orientations, and political causes. She hopes that writing and reading will force a transformative encounter “between those in the so-called free world seeking personal and collective freedoms and those in captivity seeking liberation from economic, military, racial/sexual systems.”

A3N: Andrea Smith, co-founder of INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence argues that “the criminalization approach proffered in the mainstream anti-violence movement doesn’t work. And, also, this criminalization approach obfuscates the role of the state in perpetrating gender violence.” What do you think is the best way to reduce and prevent violence against women both inside and outside prisons?

KW: Andrea is right, and over the past dozen years or so, there has been a growing challenge from women of color working on anti-violence issues to challenge the rush by white-dominated anti-violence groups to embrace more policing/harsher punishment approaches. (See some exceptional resources here, here, and here. Similarly, I am part of a growing movement of progressive queers who are challenging mainstream embrace of more policing and “get tough on crime” approaches to anti-LGBT violence; several progressive queer groups spoke out on same here.

The mainstream analysis leaves state violence out of the picture – but in fact, women (especially women of color who are low income) are often on the receiving end of mirror image forms of violence in their homes and communities and in the criminal legal system.

There’s no single solution to the problem Andrea names. What might work for one community may not work for another. But I do know some ingredients for approaches that might work better:

•address state violence – including the violence of the policing and punishment systems – in all anti-violence work.

• center the leadership and perspectives of people and communities most affected by state violence – people of color (including immigrants), poor people, prisoners and their families, former prisoners – in the work. Otherwise, we just replicate the idea of white people believing we are able to decide “what’s best” for communities of color.

• recognize that we can never just police and punish our way to safety. The overarching challenge is addressing systemic forms of violence, exclusion, and injustice in our communities. We need to build within a framework of strengthening community well being in which commitments to racial, gender, and economic justice has real, vibrant, ongoing meaning.

• shift the meaning of “criminal” simply from “dangerous individuals” to a more expansive vision that includes the harm done to individuals, entire communities, and whole nations by corporations, governments, and other public/private institutions.

• openly confront and challenge the ways in which violence against women – in families, communities, prisons – is mainstreamed into popular culture and marketed as a profitable media commodity.

NH: While the overall prison population has increased exponentially over the past 40 years, the female prison population has absolutely exploded. Women, especially black and brown women, are the fastest growing segment of our prison population. Many of these women are incarcerated for drug offenses and many have been victims of physical and sexual violence. Tragically theses women are re-victimized by prison.

We must resist rape culture. Rape culture describes a culture in which rape and other sexual violence are common and in which prevalent attitudes, norms, practices, and media condone, normalize, excuse, or encourage sexualized violence.

Acts of sexism are commonly employed to validate and rationalize normative misogynistic practices; for instance, sexist jokes may be told to foster disrespect for women and an accompanying disregard for their well-being, which ultimately make their rape and abuse seem "acceptable". Examples of behaviors that typify rape culture include victim blaming, trivializing prison rape, and sexual objectification. Our propensity for violence and sexual objectification are part and parcel of the hostile environment which leads to both rampant sexism and prisonization.

A3N: In her recent book Are Prisons Obsolete? ,

KW: We need to be careful in thinking about “reform” as end and in and of itself. Too often, “reform” means that we’re buying time to make sure that nothing fundamentally changes. For example, in the 1970s, many of us argued that indeterminate sentencing was being abused and demanded “reform.” What we got was a series of “get tough on crime” measures: 3-strikes laws, mandatory minimums, so-called “truth in sentencing” laws, and the bogus “War on Drugs.” Hundreds of thousands of people were swept into prisons for longer periods of time - and it's still happening.

Many people call for reforms today. Let’s get rid of prison rape. Let’s reinstitute rehabilitation. Let’s repeal certain draconian sentencing laws. All good and essential ideas. But very little – in some cases, nothing - will fundamentally change unless those ideas, and more, are advanced within a strategic framework of abolition. Why? Because if we’re not thinking “bigger,” the so-called reforms inevitably will morph into new ways of supporting the existing system. We need to remind ourselves that the first abolition struggle wasn't "realistic" - and originally, it was about as popular as the plague. White abolitionists caught hell from family, friends, neighbors, and faith communities. But it was the boldness and necessity of the vision that encouraged historic persistence and began to gain support. The Right knows the importance of the larger strategic vision that seems outrageous at first, but mainstreams over time because of the relentless pulse of national and local messaging/organizing that folds into the vision over a long period of time. Liberals and progressives in the

It is time for us to open up a fundamentally different and more expansive conversation around anti-queer violence and the creation of safe communities. A conversation emphasizing the integrity of community relationships and a radical commitment to community well being for all, not just the most socially, economically, and racially privileged among us.

Within that larger framework, practical reforms can be strategic steps toward something new. But apart from it, you can count on politicians, corporations, and do-nothing religious leaders to simply tweak the status quo – to our ultimate disadvantage.

The late, great civil rights activist Lillian Smith insisted that the realization of genuine justice depends on our willingness to pursue big ideas, to risk organizing for what we truly long for. In time, she asserted, big ideas that are persistently pursued will begin to take root. “To believe in something not yet proved,” Smith said, “and to underwrite it with our lives: it is the only way we can leave the future open.”

NH: The current conditions of incarceration in the

Included in this list are: racial profiling; excessive use of force – including use of dogs, kicking and beatings of restrained suspects with fists, batons, and flashlights; excessive use of dangerous chokeholds, "hog-ties", and dangerous restraints - including four point restraints, the "hitching post" and the restraint chair - that have resulted in multiple deaths; excessive use of tasers and chemical sprays; excessive use of deadly force; shackling of pregnant inmates; use of nudity, strip searches and sexual humiliation and assault as a source of social control; abuse of transgender prisoners; failure to curtail sexual assaults on both male and female inmates by other inmates and guards; denial of medical care or treatment; confinement of the mentally ill; medical experimentation on inmates; excessive use of "super max" and isolation confinement and brutal methods of execution, including lethal injection which fails to meet the standards set forth by the American Veterinary Association. These practices and conditions are in violation of The Geneva Conventions, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, Convention against Torture, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, UN Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention, UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners , UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials, UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials and the US Constitution’s 8th Amendment prohibition against cruel and unususal punishment.

This is surely unacceptable to civilized people anywhere and it is not incompatible to work for improvements of theses egregious human rights violations which working towards the larger goal of abolition altogether.

We can and must do both.

Our current experiment in mandatory imprisonment for non-violent offenders and mass incarceration is a very costly one. The prison industrial complex grows and profits at the expense of tax-payers, of social programs, of entire communities, of both current and future generations, and at the expense of the lives of the millions lost to its’ vast machinery. We spend billions on torturous punishment for “crimes” we could have prevented for a fraction of the costs at the beginning.

Noted author and educator Jonathan Kozol observes: “At issue are the values of a nation that writes off many of its poorest children in deficient urban schools starved of all the riches found in good suburban schools nearby, criminalizes those it has short-changed and cheated , and then willingly expends ten times as much to punish them as it ever spent to teach them when they were still innocent and clean.”

This is unacceptable. We must organize, continuing the legacy of struggle. We must come together across boundaries of national identity, gender, race, class and ethnicity. The call to social justice, especially when addressing complex and cloaked systems of racialization, requires critical and systematic documentation, the surfacing of deep political and economic structures, and bold confrontation. It requires the analytical tools and methods of multiple disciplines, as we have attempted to offer here. The dismantling of the white supremacist patriarchal capitalist machinery of criminal injustice requires coalitions between “intellectuals” of all sorts.

We must work in alliance to realize the vision that another world is possible.

--

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.