Bonding With Herman Wallace Inside a Louisiana Dungeon

By Ashley Wennerstrom

I first wrote to Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox after seeing In the Land of the Free last spring and learning of the horrendous injustices the Angola 3 have suffered. I felt compelled to offer my support and admiration for their commitment to social justice. Within just a few days, I received a response from Herman (Albert wrote me a beautiful letter the following week) and we began to exchange letters on a weekly basis. After several months of sparring about political philosophy, discussing literature, and discovering unexpected similarities, I was delighted when Herman asked me to join him for a special visit.

Two days before our scheduled visit, I received a letter from Herman explaining that he had not yet been notified of whether our visit was approved. I had to call the prison the morning I hoped to see him to learn that permission had indeed been granted. Upon my arrival at Elayn Hunt Correctional Center, staff informed me I was not on Mr. Wallace’s visiting list and would not be allowed to enter. I persisted, and staff eventually located my name on their list of approved special visitors. I was instructed to pass through a metal detector and was given a full body pat down before boarding the bus to the maximum security prison.

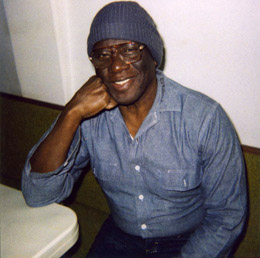

I waited about 15 minutes in a Plexiglass and telephone lined corridor for Herman to appear. When he finally arrived, clad in a denim shirt and jeans, his quizzical look instantly revealed he was shocked to

find me on the opposite side of the visiting booth. Lifting the receiver with one shackled hand, he explained that in spite of his inquiries, the prison authorities never revealed whether approval for

my visit had been granted. He was in his cell writing a letter of complaint about this lack of information when a guard informed him a visitor had arrived.

Our two hours together passed quickly, with much laughter. Herman appeared well physically and joked that “such a physique for a man of my age” was attributable to regular running on the yard (albeit in an

enclosed cage). Herman spoke slowly and deliberately. His conversation drifted between topics, but he always returned to his original point. Although he claimed to be “a little bit senile,” his memory and

knowledge of outside world was remarkable. He knew better than I the geography of the New Orleans neighborhood where he grew up and, coincidentally, I now live. He was well-versed in current politics. He referenced social media and specific websites. Only a few remarks—namely his confusion of my large, flower-shaped earrings for Stars of David—reminded me that I was speaking with a man who had been without exposure to the outside world longer than I had been alive. Herman was concerned for my safety—had I driven far in the rain?—and asked after my family. His smile waivered only when he mentioned the difficulty of not being able to attend funerals for the numerous family and friends he’s lost throughout his 44 years of incarceration. He quickly changed the subject when he saw my eyes well with empathetic tears. At the end of our visit, I told Herman that I would be honored to see him again.

One month later, Parnell Herbert and I found Herman distraught when we arrived for a visit. Prison authorities had just searched his cell to ensure that his property was “in compliance” with regulations. The thinly-veiled disciplinary action resulted in the seizure of many of his treasured photos, letters, and books. Herman realized that he had one piece of good news to share with us—his recent efforts to improve conditions had been successful. He and the other men in closed cell restriction had just been granted permission to spend an hour on the yard each day, rather than just four times each week. Herman was back to being his usual boisterous self by then end of our 4-hour contact visit, in which the three of us were allowed to hug one another, sit in the same room together, and share a meal (if hotdogs and sodas can be considered to constitute a meal).

I spent time with Herman each of the last two weekends. He remained shackled throughout both 2-hour non-contact visits. At one point a guard checked to ensure that he had sufficient slack in the restraints to be able to hold the phone comfortably, but the handcuffs were kept tight enough to leave imprints on his wrists. Herman was un-phased and jokingly bragged about his extraordinary collection of “jewelry.” Our discussions drifted between the details of his case, personal stories about our lives and loved ones, politics, our unlikely friendship, the constant harassment he endures on a daily basis, and our mutual desire to improve the lives of others. Just before our visit came to a close last Saturday, Herman asked, “What inspires you?” The answer to the question—a human who has remained principled, positive and purpose-driven in spite of living a nightmare—was quite literally staring me in the face.

By Ashley Wennerstrom

I first wrote to Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox after seeing In the Land of the Free last spring and learning of the horrendous injustices the Angola 3 have suffered. I felt compelled to offer my support and admiration for their commitment to social justice. Within just a few days, I received a response from Herman (Albert wrote me a beautiful letter the following week) and we began to exchange letters on a weekly basis. After several months of sparring about political philosophy, discussing literature, and discovering unexpected similarities, I was delighted when Herman asked me to join him for a special visit.

Two days before our scheduled visit, I received a letter from Herman explaining that he had not yet been notified of whether our visit was approved. I had to call the prison the morning I hoped to see him to learn that permission had indeed been granted. Upon my arrival at Elayn Hunt Correctional Center, staff informed me I was not on Mr. Wallace’s visiting list and would not be allowed to enter. I persisted, and staff eventually located my name on their list of approved special visitors. I was instructed to pass through a metal detector and was given a full body pat down before boarding the bus to the maximum security prison.

I waited about 15 minutes in a Plexiglass and telephone lined corridor for Herman to appear. When he finally arrived, clad in a denim shirt and jeans, his quizzical look instantly revealed he was shocked to

find me on the opposite side of the visiting booth. Lifting the receiver with one shackled hand, he explained that in spite of his inquiries, the prison authorities never revealed whether approval for

my visit had been granted. He was in his cell writing a letter of complaint about this lack of information when a guard informed him a visitor had arrived.

Our two hours together passed quickly, with much laughter. Herman appeared well physically and joked that “such a physique for a man of my age” was attributable to regular running on the yard (albeit in an

enclosed cage). Herman spoke slowly and deliberately. His conversation drifted between topics, but he always returned to his original point. Although he claimed to be “a little bit senile,” his memory and

knowledge of outside world was remarkable. He knew better than I the geography of the New Orleans neighborhood where he grew up and, coincidentally, I now live. He was well-versed in current politics. He referenced social media and specific websites. Only a few remarks—namely his confusion of my large, flower-shaped earrings for Stars of David—reminded me that I was speaking with a man who had been without exposure to the outside world longer than I had been alive. Herman was concerned for my safety—had I driven far in the rain?—and asked after my family. His smile waivered only when he mentioned the difficulty of not being able to attend funerals for the numerous family and friends he’s lost throughout his 44 years of incarceration. He quickly changed the subject when he saw my eyes well with empathetic tears. At the end of our visit, I told Herman that I would be honored to see him again.

One month later, Parnell Herbert and I found Herman distraught when we arrived for a visit. Prison authorities had just searched his cell to ensure that his property was “in compliance” with regulations. The thinly-veiled disciplinary action resulted in the seizure of many of his treasured photos, letters, and books. Herman realized that he had one piece of good news to share with us—his recent efforts to improve conditions had been successful. He and the other men in closed cell restriction had just been granted permission to spend an hour on the yard each day, rather than just four times each week. Herman was back to being his usual boisterous self by then end of our 4-hour contact visit, in which the three of us were allowed to hug one another, sit in the same room together, and share a meal (if hotdogs and sodas can be considered to constitute a meal).

I spent time with Herman each of the last two weekends. He remained shackled throughout both 2-hour non-contact visits. At one point a guard checked to ensure that he had sufficient slack in the restraints to be able to hold the phone comfortably, but the handcuffs were kept tight enough to leave imprints on his wrists. Herman was un-phased and jokingly bragged about his extraordinary collection of “jewelry.” Our discussions drifted between the details of his case, personal stories about our lives and loved ones, politics, our unlikely friendship, the constant harassment he endures on a daily basis, and our mutual desire to improve the lives of others. Just before our visit came to a close last Saturday, Herman asked, “What inspires you?” The answer to the question—a human who has remained principled, positive and purpose-driven in spite of living a nightmare—was quite literally staring me in the face.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.