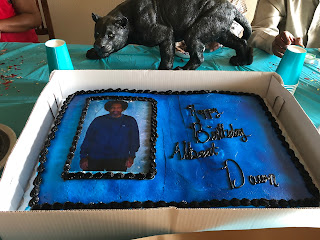

(PHOTOS: Albert's 71st Birthday party held this weekend

at his home in New Orleans. Happy Birthday, Albert!)

Albert Woodfox’s Release: Celebrating and Reflecting Upon the Two-Year Anniversary

--An Interview With Law Professor Angela A. Allen-Bell

By Angola 3 News

On February 19, 2016, following 43 years in solitary confinement, Albert Woodfox of the Angola 3 was released from prison on his 69th birthday. Now two years later, as we celebrate Albert’s 71st birthday, it is still difficult to properly articulate our profound joy that after decades of hard work and perseverance, Albert is now living life on his own terms. We would once again like to express our sincere gratitude to Albert’s legal team and to the many supporters from around the world who came together to make this happen.

Since his release, Albert has been to Denmark, Sweden, Germany, Belgium, the UK, Canada and multiple campuses including Harvard and Yale. He’s now busy writing his autobiography and both he and fellow Angola 3 member, Robert King, continue to do their best to keep the conversation about solitary confinement and political prisoners in the public spotlight.

Albert and Robert will be speaking in Los Angeles, California on April 7 at The Main and on April 9 at the Mark Taper Auditorium – Central Library. The April 7 event, moderated by artist and longtime A3 supporter Rigo 23, will occur inside the exhibition ‘Rigo 23: Ripples Become Waves,’ which takes its title from a quote by Robert King: “You throw pebbles into a pond, you get ripples; ripples become waves; the waves can become a tsunami.” A fitting metaphor for the decades-long A3 struggle.

If you have not yet seen it, ‘Cruel and Unusual,’ the UK film about the Angola 3, is now available both as a DVD and a in downloadable format through the film’s website.

Over the past six years, we have conducted a series of interviews with Southern University Law Professor Angela A. Allen-Bell. Our first interview with Prof. Bell, entitled Prolonged Solitary Confinement on Trial, followed the release of her 2012 article written for the Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly, entitled "Perception Profiling & Prolonged Solitary Confinement Viewed Through the Lens of the Angola 3 Case: When Prison Officials Become Judges, Judges Become Visually Challenged and Justice Becomes Legally Blind.”

Our second interview, entitled Terrorism, COINTELPRO, and the Black Panther Party, examined her 2014 article, published by the Journal of Law and Social Deviance, entitled “Activism Unshackled & Justice Unchained: A Call to Make a Human Right Out of One of the Most Calamitous Human Wrongs to Have Taken Place on American Soil."

Our third interview, entitled Healing Our Wounds, focused on her 2015 article, published by the University of Miami Race & Social Justice Law Review, entitled "A Prescription for Healing a National Wound: Two Doses of Executive Direct Action Equals a Portion of Justice and a Serving of Redress for America & the Black Panther Party."

This new interview reflecting upon the two-year anniversary of Albert Woodfox’s release is the third part of our most recent set of interviews with Professor Bell. Part one, entitled Plantations Were Prisons, was published during the lead up to the August 19, 2017 Prisoners Human Rights March in Washington DC, with the interview providing an in-depth discussion of the issues central to the March. Part two was published last month, following the recent decision by the California Board of Parole Hearings that granted parole to ‘Soledad Brother’ John Clutchette, where Professor Bell issued a call for readers to contact California Governor Jerry Brown, urging him to affirm the decision. Gov. Brown has yet to issue a decision, so if you have not yet contacted him in support of Clutchette’s parole, please do so today.

Angola 3 News: As we human rights activists move forward and continue fighting against the myriad of injustices related to the US prison system, it is important that we be optimistic and remain hopeful that change is possible.

You have been visiting Albert at his home in New Orleans. Can you tell us about your visits with him? Given that you visited him while he was still imprisoned, how did you feel when he was released? What’s it like now to be spending time with him outside of the prison walls?

Angela A. Allen-Bell: Those of us who served on the Angola 3 advocacy team approached our work as if victory was our only option. The only issue was when. All three members of the Angola 3 achieved freedom. This case perfectly illustrates your point. No change can happen if the change agent does not first conceive that it is possible. Hope and optimism are essential for anyone doing the work of social change.

Albert Woodfox has defied so many odds. Despite forty-three horrific years in solitary confinement, he has willed himself to be a survivor and not a victim. He astutely spent his prison days planning for freedom, often studying newspaper advertisements to keep abreast of changes. This has helped him tremendously because he never became fully institutionalized. Therefore reentering the world he left over forty years ago has been a lot less difficult.

He budgeted on the inside for freedom and lives accordingly. On the inside, he planned how he would live his purpose on the outside. He does exactly that by educating, motivating, empowering others and advocating for needed social and criminal justice and human rights changes. He travels regularly to speak and interview and is comfortable doing so alone now. Within a few weeks of his release, he learned to email, text and use the Internet. He has purchased a vehicle and a home.

On a recent visit, I got emotional seeing him walk towards the door of his home to let me in. I was overcome with emotion just thinking about our many prison visits where we discussed how this would one day be. He is at peace, finally. This has been amazing to behold.

He has reunited with his daughter and gained grandchildren and great grandchildren. They are always present or near.

The advocacy team lives on. He would probably say we are too present at times. We all call, text, email and visit regularly―just like old times. We pry and we police. He lets us in and shuts us out. We understand because this is what we fought for: his freedom. In the past two years, we have gathered for events, parties and reunions or just because. Albert is loved and revered. He smiles gently when we discuss this. He never focuses on what went wrong. He often discusses how to make things right. He is still very politically conscious and he still enjoys a good debate.

Albert is principled. He has now met public officials, celebrities and dignitaries; yet he remains a humble man. I often tell him how he exemplifies all the traits of Christ. Like Robert King and Herman Wallace, he is very true to his Black Panther Party (BPP) ideals: service and empowerment. I view him as family and I am honored to call him my friend. Astonishingly, he is now turning seventy-one years old, has experienced only two years of freedom, but mostly talks about the work he needs to do to improve prison and human conditions.

When Herman and Albert were released, it was exhilarating! The first emotion was joy (for them). The next emotion was pride (for the group accomplishment). Those two emotions were short-lived. Reality set in quickly. The reality is that, with their release, a task was completed, but the job was far from done. Like the other advocacy team members and right alongside King and Albert, with no break in time, we returned to our respective work fighting injustice.

A3N: What did you learn from studying the decades-long struggle for the release of Albert, as well as Herman and Robert –including from your personal involvement with the A3 Coalition in recent years? Are there any lessons that we can apply to the broader struggle against mass incarceration and for the human rights of prisoners?

AB: 1) Victims of injustice should never limit their efforts to participating in legal proceedings. The Angola 3 had both a legal team and an advocacy team. They had a distinguished team of lawyers and those lawyers played a pivotal role in their freedom. They had an advocacy team of people who, for years, worked tirelessly behind the scenes making sure their plight was brought to the forefront.

There are people who worked over twenty years, others who worked a single year and many more who worked spans of time in-between. The team consisted of activists, childhood friends, academics, various artists, students, citizens of Louisiana and other states, clergy members, members of the faith community, lawyers, family members, members of the international community, prisoners and members of the BPP. We did interviews, articles, plays, exhibits, prayers services, second lines, rallies, press conferences, lobbying and more.

I am convinced that the Angola 3 members would still be behind bars were it not for all of these collective efforts. What plagues me is knowing that there are many more incarcerated like Albert Woodfox, Robert King and Herman Wallace who can’t mount such a campaign. No system should operate this way, but ours does. I firmly believe defendants must fight in court and out of court simultaneously. This case teaches that lesson.

2) I have now had time to reflect on why it is that some state officials tried so hard to prosecute three men when there was no physical evidence to justify these prosecutions and in defiance of opposition from a strong, local, national and international coalition.

Time has brought some clarity. I see it as an effort to make a public example out of those who dare to confront injustice. In the early 1970s, the Angola 3 brought BPP teachings into a segregated prison, which happened to be a former plantation. They were teaching male inmates that manhood carried responsibilities, such as confronting injustice, bettering society and demanding basic human and civil rights. Men who subscribe to this thinking are a threat to plantation culture (which is what all prisons are). Plantations run best with people who passively accept their fate. They were to be living sacrifices.

My theory gained clarity as I studied the unsolved 1972 assassinations of Denver Smith and Leonard Brown on the campus of Southern University in Baton Rouge, where I teach today. Incidentally, these murders occurred a matter of months after Albert and Herman were taken into custody for supposedly murdering a prison guard. In 1972, students at Southern were actively protesting campus conditions, as well as segregation and employment discrimination in the City of Baton Rouge.

Stokely Carmichael and Louisiana’s own H. Rap Brown (now known as Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin) were invited speakers at times. State officials branded the students radicals. After a number of police calls related to protests on and off campus, law enforcement showed up in November 1972 with tanks and military weapons. Within minutes, they shot into the crowd, assassinating Smith and Brown, innocent bystanders. This caused a break in the protests that had ravaged Baton Rouge. This illustration reinforces my earlier point concerning the time-tested methodology of silencing dissent through targeted, public punishment.

Also consider the 1811 Louisiana slave revolt where over two hundred slaves led a revolt that is believed to be the largest act of armed resistance against slavery in United States history. After the organizers (Kook, Quayman, Boukman, Harry Kenner and Charles Desponded) and slave fighters were caught, some were killed and others were prosecuted and sentenced (after unmerciful beatings and torture sessions). In the end, dismembered bodies and heads were placed on poles and put in view for other slaves to see the costs of getting out of line.

Angola 3 teaches that activists must not be naive when they take public positions. They must be aware that the reaction will be to silence them and to make an example out of them. They must operate with support and never alone. Supporters must be aware of this psychological approach to destroying movements. The activist community must know that this work is not glamorous or lucrative; it is sacrificial and dangerous.

3) The Angola 3 story demonstrates the need for broadening the scope of prison reform and broader injustice discussions from a national one to an international one. It is my firm belief that international law is a powerful tool and one that is underused. Pennsylvania prison intellectual and activist Robert “Saleem” Holbrook authored an ingenious piece on this. In Statutory Illegitimacy and Mandatory Sentencing, he writes:

[T]he Civil Rights Act of 1964 essentially invited black people into the house of governance but with the condition that we come in and not touch or disturb anything, as if centuries of racial hatred, discrimination, slavery and segregation had not existed or been maintained by the government.

*****

Only an aggressive radical human rights strategy and posture will erode and delegitimize structural racial discrimination as a first step towards eventually dismantling an oppressive system that perpetuates white majority rule at the expense of black empowerment and self-determination.

While in custody in Canada, BPP member Larry Pinkney successfully self-authored a case to the United Nations and there are a number of ongoing efforts to document human rights violations. In Pennsylvania there is a prisoner-led effort called, The Human Rights Coalition. Human rights are fundamental rights that every human is entitled to enjoy just by virtue of being born. Human rights tenants were a cornerstone of Angola 3 advocacy strategy. This should be put to broader use.

4) The Angola 3 story teaches that profound misunderstandings about the BPP still exist. The Angola 3 joined the BPP during their incarceration. In fact, they began a prison chapter at Angola in the 1970s. Louisiana prosecutors and prison officials used their BPP affiliation to create a negative narrative around the case.

For years, this strategy was effective when it came to jurors and members of the public who lacked any knowledge of the case. However, the truth is that the BPP was not a terrorist organization or a hate group, nor were they anti-white or anti-government. They are not akin to the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) and they should not be compared to them. The KKK formed to promote white supremacy and racial separation. The BPP formed to eliminate injustice, empower people and improve conditions for them.

The BPP did not believe in pleading, begging, praying or patiently waiting for equal rights to be conferred. They felt that equality was a birthright, demanding it was a duty, having it delayed was an insult, and compromise was tantamount to social and political suicide. They were largely victims of a sinister plot by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to destroy them because he was irrational, racist and opposed to dissident views of any sort.

While the BPP’s organizational life span lasted sixteen years, their contribution to society continues. A Citizens’ Complaint Board to hear allegations of police abuse was established by the Oakland City Council in 1981—fourteen years after the BPP launched its community patrols of the police. This model has been replicated and reused. Their effective use of multicultural alliances is a model that has been replicated and reused. The BPP’s breakfast program and food giveaways raised public consciousness about hunger and poverty in the United States. These programs were a precursor to the present free school lunch program. BPP activism provides a model for community self-help. Additionally, their efforts where Sickle Cell Anemia was concerned laid the groundwork for our current medical awareness and response.

In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, it was the ingenuity and the selflessness of some BPP members that saved lives and rendered aid to many New Orleans residents when an official governmental response was still be fashioned. These individuals used the BPP party platform and organizing strategy to form a highly successful multicultural coalition of national volunteers who assisted for months following Hurricane Katrina.

BPP members understand how to put loyalty into practice. I joined the advocacy team when Robert King was already free. His twenty-nine years in solitary confinement did not slow him down when it came to matters of freedom for Herman and Albert. He maintained a prominent role into the inner-workings of the advocacy and litigation teams and traveled the globe to bring awareness to the case when he could have chosen to enjoy his freedom. His sense of brotherhood, his energy and his commitment to the cause was a constant inspiration to the group. Angola 3 teaches that not enough effort has been made to redress victims of J. Edgar Hoover’s COINTELPRO tactics and not enough has been done to correct the historical record where the BPP is concerned.

5) This case also holds valuable lessons when it comes to political and politicized prisoners. It highlights our failures where they are concerned. There are many more political and politicized prisoners who have been behind bars from the civil rights era. The National Jericho Movement’s list is a trusted source. I would also add Louisiana’s Kenny “Zulu” Whitmore, who was recently released from over twenty-eight years of solitary confinement, and seventy-four-year-old John Clutchette to that list.

John Clutchette is the sole “Soledad Brothers” survivor. He should be a free man today. The parole board has granted parole several times, including most recently on January 12, 2018. In 2016, California Governor Jerry Brown reversed them, citing his affiliation with George Jackson and the 1970s Soledad Brothers case despite the fact that he was acquitted of all charges in the Soledad Brothers case.

Governor Brown has not yet decided whether he will affirm the recent January 12, 2018 Parole Board decision granting parole (as publicized by last month’s Angola 3 News interview where I shared details of a restorative justice project my Law & Minorities students undertook and called upon readers to act by contacting Governor Brown to express their support for parole in John Clutchette's case).

It is time for us to become concerned about the plight of political prisoners, which, by the way, is yet another human rights violation. Many of them don’t get visits, don’t have funds or support from the outside and are routinely subject to abuse from prison officials. We celebrate the heroes we have been trained to embrace and overlook these individuals. We need to change the narrative. The Angola 3 case underscores this.

6) The Angola 3 case teaches about the importance of interconnectedness. As members of the human family, we are duty-bound to take care of our own. No one is exempt from this work. In the words of the late Derrick Bell:

We must complain. Yes, plain, blunt, complain, ceaseless agitation, unfailing exposure of dishonesty and wrong――this is the ancient, unbarring way to liberty, and we must follow it.

The late Reverend Martin Luther King also urged this:

In a real sense, all life is inter-related. All persons are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be, and you can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be. This is the inter-related structure of reality. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.

This was put into practice by the volunteers who interrupted their lives to lend a hand to the cause. This template should be duplicated by others.

7) This case highlights the importance of contextual evaluations of injustices, which requires both historical cognizance and analytical fortitude (skills we must ensure that all youth and all social change agents possess). In 1971, the 26th Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified. It gave 18-year-olds the right to vote. Public protests, challenges and activism were of tremendous concern during this era because of the potential influence they could have on this new, impressionable pool of voters. This presented specific concerns for President Richard M. Nixon as he geared for reelection.

Without attention to this historical reality, allegations of men murdering an Angola prison guard in 1972 could be accepted at face value. When this layer of context is added, a more expansive view of the case takes form. The listener hears the allegation, but also sees the context within which they arise, causing the murder allegations to compete with the vivid reality that men who had proven that they could successfully organize a following to oppose, question and challenge norms could contagiously impact an area, then a region, then a nation.

Another lesson that the Angola 3 case offers is that injustices should never be viewed out of context.

A3N: Any closing thoughts?

AB: I had the good fortune of visiting with Angola 3 member Herman Wallace during his incarceration and seeing him the night of his 2013 release and in the short days to follow before he succumbed to the cancer. When he was released, he was a very sick man, but he was well aware of the fact that he had achieved freedom following the court’s ruling declaring him to be a victim of grand jury discrimination.

From the time I met him until the time he left this world, Herman spent his time in service to humankind. He looked out for inmates in need, he fought for prison policy changes and he devoted himself to social progress. He was a shrewd organizer and a clever teacher, both by his words and his example. I am a better person because of the time I had with Herman. He badly wanted to see an awakening in this country. Prison organizing and riots have historically resulted in gains for inmates. They have also served as a vehicle for getting the public’s attention on prison affairs. I will conclude by reflecting on Herman’s words:

A Defying Voice

They remove my whisper from general population to maximum security

– I gained a voice,

They remove my voice from maximum security to administrative segregation

– My voice gave hope,

They remove my voice from administrative segregation to solitary confinement,

-My voice became vibration for unity,

They removed my voice from solitary confinement to the Super Max, Camp J

-Now they wish to destroy me,

The deeper they bury me, the louder my voice.

I SAID – THE DEEPER THEY BURY ME, THE LOUDER MY VOICE!

By: The Late Herman Wallace, Angola 3 member

--Angola 3 News is a project of the International Coalition to Free the Angola 3. At our website, www.angola3news.com, we provide the latest news about the Angola 3. Additionally we create our own media projects, which spotlight the issues central to the story of the Angola 3, like racism, repression, prisons, human rights, solitary confinement as torture, and more.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.